Immigrants in Germany and in most of the Western world today are met with mixed emotions. Syrian refugees are granted a place to stay temporarily, but the European public is suspicious of what migration might bring. While in many parts of the world, immigrants are totally demonized and outlawed by people like Trump, Wilders, and other politicians.

Migration, travel, and interaction with different cultures is an age-old phenomenon. During the 1800s, European powers scrambled to gain control of different countries in Africa and Asia and claim ownership of their natural resources. Although Germany is not known for its colonial power globally, as the Dutch and the English were, the governor Bernhard von Bülow is known for saying: “We wish to throw no one into the shade, but we demand our own place in the sun.” In 1897, Germany, with its relatively relaxed approach to colonialism, took over countries that were lesser in demand like Namibia, Papua New Guinea, South West Africa, Ghana, and Togo. Little is remembered in Europe of these events today, despite an undoubtable German influence.

In Cologne, there is a museum called the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum where large collections are housed of objects that were taken by different geographers, ethnographers, and explorers through the years. Two of the most interesting are from Max von Oppenheim, a wealthy diplomat, and Wilhelm Joest, a wealthy scientist. Max von Oppenheim is best known for his “discovery” of the famous site in Northern Syria called Tel Halaf, for which he constructed an entire museum in Berlin.

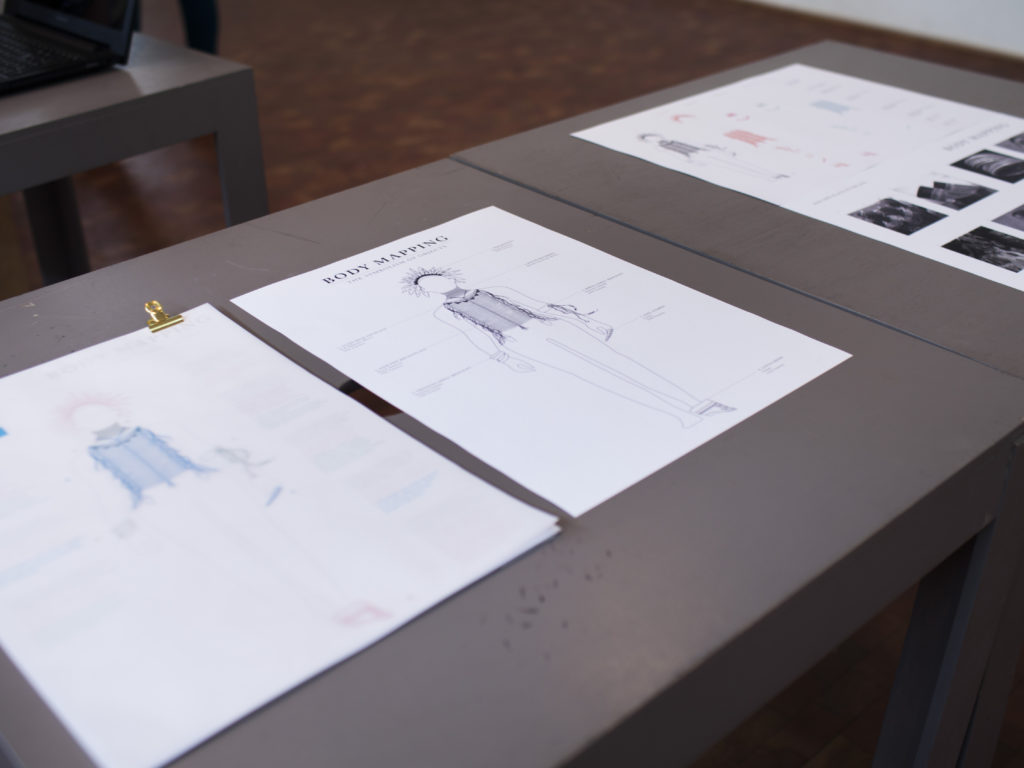

Eighteen students were asked to select an object of their choice from the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum collection and to investigate its origin and symbolism. Students worked in groups to remap objects by critically reconsidering their relevance as objects which have been removed from their colonial context. What is the current function, meaning, and contemporary understanding of these objects which have found a home inside the famous German museum?